A grubby homeless guy haunts a tube entrance, a limousine lumbers by. A sleek courier glides through the growls of snarled traffic. Pizza chains blithely squat beneath the unabashed grandeur of ancient mansions, now part of the same tourist circuit. The windows of a bank you've heard of advertise the usual stuff; the one opposite which you haven't offers you-don't-understand-what. Somewhere a wallet is being stolen. Somewhere a fortune being made. Somewhere a heart is broken by text message in a foreign language. A camera flashes from the top of a bus. Every third shop sells coffee and sandwiches.

The usual London just outside my office, in other words. Except not this week, at least not for me. Tuesday afternoon, half one. A five minute walk from my office and I push my way through the old, heavy, creaky wooden doors of Simpson's-in-the-Strand, and enter another world. I've not been here for just over a year, when I watched the last Staunton Memorial. But not much has changed. And not much will. There's still the display case of slightly random chess memorabilia in the hallway. And still that remarkable 19th century chess set in a case of its own, bearing a plaque with the names of those whose hands lifted its pieces. The first three are: Howard Staunton, Paul Morphy, Wilhelm Steinitz. You can't but feel a tingle every time you read it. That close. That far away.

Through the double doors is the Grand Divan. The famous old booths lining its side like railway carriages. The silver-domed carver trolleys, ready to wheel out to your table. Do the chandeliers date from 1828, the year Simpson's opened? Maybe. The snows of an ended empire seem never to have reached this unchanging room of Imperial style, where grand old men can still cradle their last moments, like the light they cradle in their brandy glass. But I am not here to wine or dine in this antique environment. Upstairs is the chess tournament.

It's twenty minutes until the round starts. Ray Keene is wondering where the programmes are, explaining to someone that they're priced £2

not in order to actually sell them, but so that

those people who snaffle lots of them will feel guilty. Arbiter Eric Schiller - who looks dressed for a Californian beach, albeit the hot-dog rather than surfer end - goes chirpily about setting the clocks. They're electronic this year. A first for this tournament, a first for Simpson's no doubt too. It's the same room as last year, with its subdued splendour: the ceiling not miles away, the lights gentle rather than blinding, the carpet comfortable rather than lush, the columns intricate rather than brutal, the wall paintings more background than eye-catching. A few improvements: the playing tables are better angled for the spectators, and water is provided for us too this time.

Two o'clock and Keene gives a little speech, thanking those to be thanked, going over the particulars, and recounting the story of how the Immortal Game was played here. Immediately after it finished, he says, spectators sprinted off down the Strand to telegraph Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky's moves around the world, or what they thought were the moves. Is that true? I can't be the only one to wonder, but it doesn't matter. The story fits the nostalgic mood somehow.

He announces another improvement on last year: all of the moves will be broadcast live. This sounds good, I think. Last year

none were broadcast live at all, not even one. Well, Keene says, broadcast on a rotating basis: two of the games will be broadcast live, then a little while later, another two, then the final two, and so on rotating through out the afternoon. Broadcast, that is, via a video feed of the display boards - not PGN, not MonRoi. And .... broadcast where to? To the aptly-named Knight's Bar in Simpson's itself, just across the hall and around the corner, where Bob Wade will lead the conversation about what's happening on the boards. And that's it.

The rest of the world is not amused, but it's hard to know if this is genuinely lackadaisical, or deliberately acommercial, or passively-aggressively out-of-date - or more just a throwback to a more stately pace of life, a more intimate organisational ethos.

Ray says he's confident the system will work. But then points out, the system also requires the display boards in the playing room to be right. And then the fellow whose job this is interrupts Ray - saying he agrees, and how he remembers

the comments from last year. It's obvious Ray suddenly remembers too: The display boards were more or less a shambles throughout the tournament last time around. Ray starts to repeat, more than once, how important it is they're right this time. Really important, because of the video relay. Vitally important.

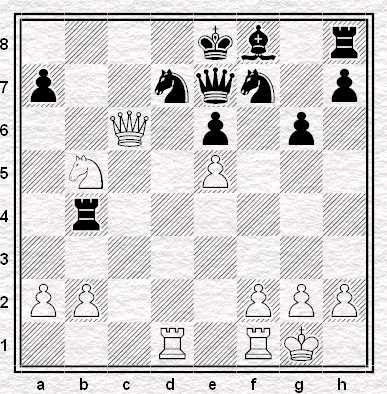

Big job, Alexander. As it turns out, today Adams's display-board king will stay on g1 for several moves more than it actually did, but apart from that I didn't spot another error in the half hour I was able to stay in the early afternoon. A big improvement on last year, trust me, when captured pieces stayed on the board whilst others fell off arbitrarily, and so on.

The Orange Dream Team, as the Dutch team are called, waft in collectively first - this by accident rather than design, with the British drifting in soon after. Gawain Jones is one of the last; but at nineteen, is a brand new GM. Strapping is the only word, and still growing too one presumes: his trousers are two inches too short. (He will do well to hang on to draw in the first round, after his opening looked to go really quite wrong against Jan Smeets.) Amongst the others, there's the usual chess player mishmash of clothing styles, from jeans and hoodies to suits and ties. Surprisingly Jon Speelman is one of the smartest: not only wearing a suit, but this year also

not bringing his belongings with him in a supermarket carrier bag.

A sign of more circumspect things to come than 2006's over-the-board disappointments? Fast forward to the end of the first round: He and Jan Timman certainly produced one of the most intriguing games, an original encounter I don't pretend to fully understand - nor why Timman who beat Speelman last year agreed a draw at the end. The best game of round one however would stem from the most surprising result: Colin McNab's victory over Ivan Sokolov, a piece of hypermodernism that wouldn't have looked out of place in a Reti game from the 1920s. An especially fine achievement given the rating difference, and that Sokolov ran away with the tournament last year without losing a single game. Meanwhile the opening in the game between Erwin l'Ami and Peter Wells looked entirely violent and with various bits hanging as if anything could happen. But it suddenly petered out to a flat draw - like an amusing balloon parping fleetingly around a party, only to collapse and crumple quickly in the corner. Jovanka Houska seemed to lose the plot in a double rook endgame against Jan Werle, but perhaps there was more to it than that.

Newly-married Michael Adams was content with a short draw against Loek van Wely - 15.h3 is perhaps the definition of limp - which probably indicates something of his tournament strategy: draw against anyone who might have a chance of beating him, try to win against the rest. van Wely won't mind presumably such a gentle first round draw with black, and against the only player in the tournament rated higher than him as well. Here are the best two games from the round:

McNab-Sokolov: 1. Nf3 d5 2. g3 Bg4 3. Bg2 Nd7 4. d3 e6 5. Nbd2 Bd6 6. h3 Bh5 7. e4 c6 8. O-O Ne7 9. b3 O-O 10. Bb2 a5 11. a3 f6 12. Qe1 e5 13. d4 Qc7 14. c4 Bxf3 15. Bxf3 exd4 16. exd5 c5 17. Qe6+ Kh8 18. Ne4 Nc8 19. Bg2 Ra6 20. Nxd6 Nxd6 21. Qe2 a4 22. b4 b6 23. Bxd4 Raa8 24. bxc5 Nxc5 25. Rae1 Nb3 26. Bc3 Rae8 27. Qh5 Qxc4 28. Bb4 Nc5 29. Rc1 Qb5 30. Rfe1 f5 31. Rxe8 Rxe8 32. Bf1 Qd7 33. Bxc5 bxc5 34. Rxc5 Ne4 35. Bb5 Qd8 36. Qxe8+ Qxe8 37. Bxe8 Nxc5 38. d6 Kg8 39. Bxa4 Kf7 40. d7 Ke7 41. Bb5 f4 42. gxf4 Ne6 43. a4, and black resigned.

Speelman-Timman: 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 b6 4. Nc3 Bb7 5. Bg5 Bb4 6. Nd2 h6 7. Bh4 Nc6 8. e3 Ne7 9. Bxf6 gxf6 10. Qb3 c5 11. O-O-O Nc6 12. Nde4 Na5 13. Qc2 cxd4 14. Rxd4 f5 15. Nd6+ Bxd6 16. Rxd6 Rc8 17. Qd2 Qe7 18. Be2 Nxc4 19. Bxc4 Rxc4 20. Rd1 Bd5 21. Rxd5 exd5 22. Qxd5 Rc6 23. Qxf5 Qe6 24. Qd3 O-O 25. Qxd7 b5 26. Qb7 a6 27. Rd4 Rc4 28. Rxc4 Qxc4 29. Qxa6 Qf1+ 30. Kc2 Qxf2+ 31. Kb3 Qxg2 32. Qxh6 b4 33. Na4 Re8, draw agreed.

Rewind in time, and back to my office after half an hour and the opening moves I go.

But after work I return again, and on this visit a few programmes lie around the tables. So what else to do? I pick one up and start reading it. No-one asks me for money, no-one notices; it's mine now. Flimsy, in parts ineptly written, cheaply produced, with a terrifying image of Staunton on the cover - he looks completely demented - and I start to wonder if even free is too much. But gratitude becomes me, and a closer read later locates in it the odd intrigue. As an off-hand example, here's two quotes from the programme's biographies that might act as circumstantial answers for

some of the questions here: "Jan [Smeets] became a grandmaster in 2004 and dabbled for a while at being a full-time professional, but cited the unexciting periods between chess events as a reason to become a full-time student in economics at Rotterdam University." Similarly, GM Jan Werle, the programme reports, "tried going professional for a year but did not care for the lifestyle and is now a law student in his home town of Groningen."

A tap on the shoulder: an old friend. We gesture to go outside to have a chat, and as we do so a phone goes off somewhere in the room. A few heads shoot up sharply, but then all turn to smiles. Jan Mol's phone. Jan Mol, generous sponsor and more or less host. Jan Mol, darting out looking only a touch sheepish. He can make whatever noise he wants, we suppose - but we can't, and our chat leads us out to the nearest pub; the price of drinks in Simpson's itself are firmly not rooted in the past.

It's almost seven when I return to check on the games - and, nothing. The arbiters and officials are all departed; a few chess players casually analyse in the bar, where the scent of the first of the evening meals deliciously circulate through the luxurious chattering air. The lights are out in the playing area, but I push through the doors anyway, to have a poke around, one last look for today. The final positions are up, and I raise my eyebrows at more than one. Jones drew? Sokolov lost! Timman and Speelman agreed a draw

there? It's strange to wander through the chairs and the boards and the clocks alone, as invisible as a ghost.

No-one has stopped me coming here, asked me what I'm doing or where I'm going. But no-one ever checks anything like that in Simpson's. If only the grubby homeless guy knew how easy it was, I think stupidly to myself, to find oneself amongst this rich and refined corner of quiet and comfort. But he'd never get through the revolving doors.

Not confident they'll appear on the website, I decide to jot down the final positions from the display boards. Black, gold lettering, triangular - one of the Simpson's pencils left by one of the boards looks rather dapper. Feeling entitled I start to write with it: and accidentally jab my finger. Blood and a sharp prick of pain come quick. Underneath such a casually charming appearance, it turns out to be as sharp as hell.