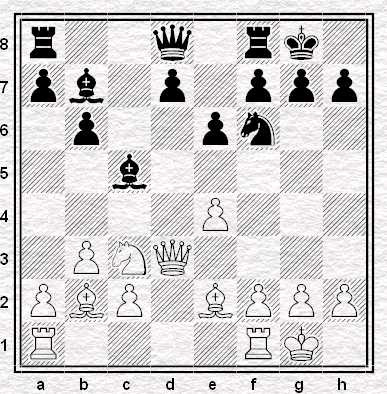

Have a good look at the position below - it's Black to play - and decide what move you'd like to play.

Take your time. Take as long as you like.

.png)

It's the sixth and final round of a Lloyds Bank Under-16 tournament in 1981. I have accumulated three and a half points out of five and I have the Black pieces in the final round. My opponent has erred slightly in the Najdorf theory which I then felt it necessary to know, because having castled earlier than is recommended, the subsequent knight check on d6 allows a winning queen exchange (via the check on d4) if the capturing bishop is then recaptured. Noticing this, he has decided to play the position a piece down and gone

20.Qd2-g5!?!

He took this decision really quite quickly - just a couple of minutes' thought. But I, having taken only about ten minutes to reach the diagrammed position, thought for much longer. Much, much longer. I thought for longer than I had thought over any move I had played in my life. In fact I thought for so long, not only did my opponent get up several times from the table, I actually did the same myself. Twice.

Without going into detail (or caring to) the point is that Black's king, not unusually in this variation, is in serious danger. After the threatened check on h5 there may be no easy escape for it towards the queenside given that the queen may come to the seventh rank. This might mean that bringing the queen rook to the rescue via a7 might lose that very rook to a skewer: meanwhile although Black still has a free check on d4, is this actually a good idea given that White can put rooks on d3, or d1, or both?

By the time I was ready to select a move, forty-seven minutes had elapsed. I chose the queen check

20...Qd4+ which is actually a good move, quite possibly a winning one: the follow-up, after

21.Kh1, of

21...Ra7 is less strong (

21...e4! is the computer's choice) but still seems to hold the draw. However, I was under real pressure now (though not particularly from the clock) and after

22.Bxh5+ Rxh5 23.Qxh5+ Rf7 24.Rd3 Qc5 25.Rfd1 Be7 26.Rg3.png)

I failed to find the one saving move (you may like to locate it yourself) and after

26...Qxc2?? succumbed to a mate in four. There was some sort of extra incentive for the prizewinners, a place in the Lloyds Bank Masters or the BCF junior squad or something, I forget what: as it was I finished half a point short and was never heard of again. And it's a good thing too.

I've always remembered those forty-seven minutes though: since then I've twice had opponents think for an hour or more on a single move, but never got close to it myself. Until, that is, the Saturday before last, playing the

Breyer Variation against Zaragozan FIDE Master Fernando López Gracia, when after White's

22.Nh4-f5! I found myself in the following position.

Once again, take as long as you like. Or at least, take up to an hour - because that's how long I took. Maybe an hour. Maybe more.

Why? The simple answer is "because I didn't know what to do". The more complex explanation is that at first I thought I must be winning, then I thought I must be losing and it took me the best part of an hour to decide that I had no alternative that I could rely on.

I was under the impression, in the first place, that I had done nothing wrong and that therefore the sacrifice must be unsound. (This isn't right, as it happens: the bishop belongs on e7, not g7 and for that matter the queen has probably gone to the wrong square.) But the more I tried to find the winning line, the more I found myself looking at a sequence such as

22...gxf5 23.Bxf6! Bxf6 24.Nxh5 and after that the queen comes to g5 or h6 and Black never, it seemed to me, quite has the time to play

....f4 before White plays

exf5 and the bishop or the rook, or both, join the attack.

I spent a long time trying to work out if I had a defence after

24...Bh8 and never, quite, deciding whether I did or whether I did not. The problem was, that if I had overlooked so much as a small detail, my king was open and alone with the White pieces homing in on it: however, if I was right to take - and I was

sure that in principle I would be - then the right sequence would win the game for me. I was aware that I was taking too much time: but at the same time, I was aware that it might be worth it.

Moreover, if I did not take, then what should I do? I didn't fancy

22...Bh8 very much (besides, he seemed to have the promising sacrifice

23.Bxf6 Bxf6 24.Nxh5 so I wasn't saving myself any bother that way) but the only other idea I had would be taking witha knight on e4 and then picking up the f5 knight at the

end of the sequence, e.g. something like

22...Nfxe4 23.Nxe4 Nxe4 24.Bxe4 gxf5 25.Bxf5. However, although that might constitute a way not to get imediately mated, I couldn't look at the resulting position, by any means that I tried to achieve it, and tell myself that I had anything other than I prospectless position that my opponent ought to find it very easy to win.

And yet, you know, if I take on f5 I might be winning...We each had ninety minutes for the game, plus thirty seconds a move. I'd actually played the first eighteen moves almost instantly, such that my side of the clock showed ninety-eight minutes, a very rare occurrence at that time limit. I took a few minutes apiece over the next three moves (I'd always previously played

19...Kh7) and neither my handwriting nor my memory is such that I can be sure how many I had left before, or after, my 22nd move. This time I didn't get up: I sat and thought, and sat and thought, and eventually decided that

some sort of tactics were surely in order if I were to give my opponent a chance to go wrong. So I did indeed play

22...Nfxe4 and he chose

23.Bxe4, which is good, and then after

23...gxf5 selected

24.Bh6, which is not. He'd missed my

24...f4! after which, amazingly, despite my open kingside and his three pieces within it, I was back in the game:

and after his further error

25.Bxg7? and my second consecutive surprise failure to recapture,

25...Nb3! I was, strictly speaking, winning.

It's not the fork that matters - Black will be very lucky if he gets time to take the rook, though naturally it doesn't hurt to be threatening it - so much as the fact that White needs to move the queen and has no useful square (he'd like a dark one on the kingside) to move it to.

Now it was his turn to think long and hard and eventually the game continued

26.Bh7+ Kxh7 27.Qc2+ Kxg7 28.Nxh5+ Kh6 29.Nf6 Rh8 30.Qf5 and although Black had played seven consecutive good moves with hardly any time on the clock, the eighth proved beyond him and he played

30...Bc8?? which loses a won game.

White played

31.Ng4+ Kg7 32.Qf6+ Kg8 33.Nxe5. This is what Black had overlooked - the knight cannot be captured because the b6 queen is loose. (

30...Qd8 or

30...Qc7 are promising.)

33...Qb7 34.Nc6 Rh5 35.Re8+ Kh7 and Black resigned.

Twenty-eight years, less a month, between two games: in some ways it seems less than the hour between two moves. Because the games look and feel so very similar, as if nothing had changed in the player of the Black pieces, from the fifteen-year-old boy to the middle-aged man. On the board, everything changes in an instant: let alone in the eternity of a whole hour. But nothing really changes. Not even in half a lifetime.

If time means anything, it is, where I am, still five minutes short of noon. But for some reason I think I need a drink.

.png)

.png)