We have been rooting around in the nooks and crannies of Anthony Rosenbaum’s chess picture and, as we've gone along, we've noted its public appearances. Here is another one:

|

| From Matthews British Chess (1948) Find out who everybody is here. |

Now we turn to look at a man whose time has come, in this series anyway: Wordsworth Donisthorpe (1847-1914) - about whom, with the generous help of others, there is much to tell, which for the chessers of the period outside the first rank is perhaps unusual, but he was no shrinking violet and so left a heavy footprint in the historical record, of unusual breadth and depth to boot. He is sitting, and reading, in the bottom right-hand corner.

A thoroughly researched account of his adventures by Stephen Herbert and Mo Hearn Industry, Liberty, and a Vision (1998) has brought much to light, and in particular does full justice to him as an inventor. It also mentions his chess. For other important chess data see Batgirl's helpful blog here, and there's a mention in Tim Harding's Victorian Chessers book.

With this episode, as with all of them, the usual caveats apply: all misrepresentation, misinterpretation and narrative overexcitability are the responsibility of the author.

To begin with let's remind ourselves of how Rosenbaum painted him. Here's a man who ploughed his own furrow, and dressed for the part. Not, though, in cloth cap and clogs. He is Wordsworth Donisthorpe à la mode, a dedicated follower of fashion.

|

| Because I'm Wordsworth it. |

Chess-wise he was strong, if not quite in the top flight. Initially he had been a "pawn and two" player, according to an appreciation in The Chess-Monthly of December 1890, but latterly "an amateur of the 1st class", and with Bird's (balding, seated behind the board top-left) commendation. In wider chess matters he was a full-blooded mover and shaker, taking a role in club governance (British Chess Club Vice-President, for example, in 1885), voicing opinions on proper national arrangements (e.g. a revitalised British Chess Association, of which he was a founding Council member the same year),

and tournament administration (he was on the Management Committee of the 1883 London International). In the Saturday Review of 1893 he proposed a rule amendment to permit the king to be captured, thereby eliminating stalemate and as a by-product reducing the number of draws (see Batgirl). It has yet to catch on.

By the time of the

unveiling of Rosenbaum’s picture in 1880 Wordsworth (his mother claimed to be the

great-niece of the poet) he had already made his mark. Back in 1876 he'd applied

for a patent for an “apparatus for taking and exhibiting photographs”- moving ones - and in that year he'd published his first political tract The

Principle of Plutocracy which “ investigates the law of value…and the source of wealth”. This was after his studies at Cambridge

|

| A kind of 20th Century Wordsworth Donisthorpe. |

His many talents include his wit and banter - even at the board apparently - which survives in his copious writing. A chess-related example would be his “poetical alphabet” which, said The Chess-Monthly of January 1895, "rightly or wrongly, is attributed to the gifted pen of the genial philosopher Wordsworth Donisthorpe" and for legal reasons was not formally acknowledged as by him, indeed one stanza was retracted for fear of litigation. The "poem" lampoons several of his fellow British Chess Club members, and the three who are in Rosenbaum’s picture are given below. Although you are a contemporary reader, and are not easy to shock, be warned: these extracts are really rather

tame.

On the green-baize skills of the editor of The Chess Monthly, at board two, left of Steinitz:

"H stands for Hoffer.

At chess he gives odds; / But to see him play billiards’ a sight for the gods ;"

On the classically educated, white-haired gent who stands behind the front board:

"W for Woodgate,

a walking Thesaurus. / His English is grand – but his Greek tends to bore us ;"

And, as if to put up a smokescreen as to authorship, he writes this about himself:

"D stands for Donisthorpe

; some folks complain / That he

oftener wins with his tongue than his brain ;"

Well, he said it; although he did have genuine chess success, for example when he tied with the Rev MacDonnell (bearded, two left of Bird) in the 1897 London Tournament secondary competition for participants with qualifications in “Art, Science, or Literature”. Professor John Ruskin, vice-president of the BCA, was a patron of the tournament and a selection of his works made up the prize. The cerebral side of Donisthorpe might have been pleased to add the great man’s voluminous tomes to his library as he was a fan of sorts: in "The Claims of Labour" (1880) he concurs with Ruskin's denunciation, delivered "with force and ability", of the destruction of individual craft and skill by industrial machinery. Before we move on here is another example of WD's wit, manifest this time at the board. In this little bit of nonsense the coup de grâce cannot fail to make you smile.

Something else to raise a smile is this wonderful cartoon by Harry Furniss published in Punch in 1885:

|

| Click on to enlarge |

|

As for his politics, you get the flavour of Donisthope’s "small state" (as we'd say today), "let-be" (as he said then) persuasion from this statement of aims of his

"[The League] opposes all attempts to introduce the State as a competitor or regulator into the various departments of social activity and industry which would otherwise be spontaneously and adequately conducted by private enterprise.”That came from a League pamphlet (1888) "against teetotal tyranny" written by Isidor "Mephisto" Gunsberg, no less, opposing the Temperance movement’s “Local Option” proposal for community rights to ban the local sale of alcohol. It is a pretty dry read, and one suspects the hand of Donisthorpe in this attempt to froth it up: why stop at booze - he asks rhetorically - why not also ban “meat [as it is] very generally abused by Englishmen, causing a great national evil [of] indigestion, a far more serious evil, in our opinion, than intemperance”.

Chesser James Mason (in profile, middle row, first left of page break) also brought home the bacon thanks to WD's good offices (per Tim Harding) and, what with his “The Claims of Labour” finding a publisher in Samuel Tinsley & Co. a few years earlier, chess connections were evidently proving mutually advantageous, as we suspected in episode 3.

|

| Gunsberg's 1888 pamphlet, & Donisthorpe's published by Tinsley (front row, right of waiter) in 1880. (apologies for the BL watermark) |

His thinking and interests evolved from political economy to encompass social philosophy and we find him as the President of the Legitimation League in the 1890s. It/he argued, in respect of family life, that the status of illegitimacy visited on children born out of wedlock was a misconceived notion - as you might say - and was unacceptable. Not that he was advocating anything other than monogamy, married or otherwise: it was "the highest and best state of sexual relationship". Yet he was reluctant to condemn multiple partnering ("let-be!"). "Perhaps the epicure is right in approving oysters and chablis..." - WD's lubricious trope for monogamy - but "...it may be that the coster really prefers whelks and porter, and it would be quixotic to reprove him for indulging his 'low' and 'beastly' appetite...". Chew on that.

|

| "What's for luncheon?" The Adonis around 1910. |

|

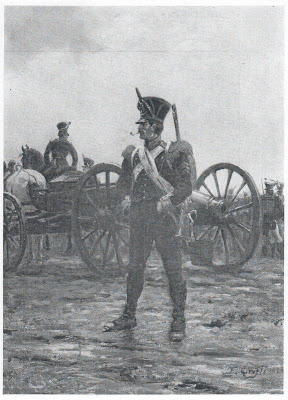

| The Advance Guard. Ernest Crofts RA (1847-1911) Image from the Witts Library. "Crofts grafi bel Kanbide men prelam" as Donisthorpe might have said. |

A recent reconstruction

of Donisthorpe and Crofts' Kinesigraph of 1889/90. |

Stephen Herbert

conjectures that there may have been, in part, a hidden agenda in photographing this

particular scene – traditionally the site, in the heart of London less than a

mile from Parliament, where freedom of speech and expression is exercised en masse in demonstrations and assemblies. Donisthorpe might have intended to

use it in his lectures to show the very place where ordinary decent citizens found that their right freely to walk the pavement, and go about their daily business, monstrously trampled by whelk-chomping trade unionists led by John

Burns and other bolshie Scots. WD's collaborator, W. C. Crofts, had written a broadside against the "Socialism of the Street in England" in 1888. The reality was however (according to Mr Herbert) that projection proved even more problematic than the initial recording. Raising funds for further development, even with Sir George Newnes' assistance, proved too much of a challenge.

That's Sir George Newnes who made an appearance in episode 5. He was, for 20 years in total, the Liberal M.P., for Newmarket and, later, Swansea; chair of both the British and City of London Chess Clubs; "reportedly the best chess player in the House of Commons" (according to G. A. MacDonnell); and publisher, from 1881, of the popular weekly, jauntily titled "Tit-Bits", from which he made his fortune.

Donisthorpe's final adventure was a kind of Eight Men in a Boat cruise around the Mediterranean with Newnes and sundry other chaps. It was written up as "Down The Stream of Civilization", and even has a literary reference chess game in the dialogue on the first page: "...looking up from the chess-board, on which he was struggling with a rather nasty attack..." ("Then give him some Beecham's", they cried?). Here he is (on our left), aka "Jus - a Literary Failure", waiting to splice the mainbrace with some fellow hearties. Newnes, "The Commodore", is on the far right, and it was he who published the yarn in 1898.

|

| Tit-Bits in 1906, offering a cure for the abuse of meat. |

Just a couple of further examples of Donisthorpe's active mind always at work, demonstrating an unstinting zeal to smooth the inner rumblings of the body politic. He devised a new language (Esperanto-style) based on Latin: "Uropa", for which he wrote an instructional exposition, the introduction to which betrays a little, rather atypical, self-doubt.

"All are requested to read through the following chapters [that's all 28 of them - MS], without mental protest [his emphasis - MS] till the end is reached. Then, but not before, let them pour forth their pent-up fury over its apparent shortcomings and defects."

Look again at that example of "Uropa" in the caption to the gay Hussar above, though it is not a phrase which, in translation, has the quotidian utility of "What's for luncheon?". "Crofts grafi bel Kanbidem men Waterloo prelam" in Uropa-speak translates, so Donisthorpe assures us, as "Crofts paints a fine canvas representing the Battle of Waterloo". Uropa didn't catch on, either.

Nor, as a lubricant to free trade, did his proposed new system of weights and measures. Though actually that's only half right, as we (here in the UK) are moving, if only half-heartedly, towards a universal decimal base such as he advocated. Perhaps, for those times, Donisthorpe made a tactical mistake in proposing a system that was associated with things French, something his novel nomenclature based on cod Olde English didn't quite disguise. After "Jot" (that's a millimetre), he has "Quil" and "Hand", but then "Mete", which was a bit of a giveaway. In money matters our man did, however, catch the eye of H.G.Wells, who was minded to adopt WD's "Lion" as the principal denomination in the decimal currency of his Wellsian Utopia.

Nor, as a lubricant to free trade, did his proposed new system of weights and measures. Though actually that's only half right, as we (here in the UK) are moving, if only half-heartedly, towards a universal decimal base such as he advocated. Perhaps, for those times, Donisthorpe made a tactical mistake in proposing a system that was associated with things French, something his novel nomenclature based on cod Olde English didn't quite disguise. After "Jot" (that's a millimetre), he has "Quil" and "Hand", but then "Mete", which was a bit of a giveaway. In money matters our man did, however, catch the eye of H.G.Wells, who was minded to adopt WD's "Lion" as the principal denomination in the decimal currency of his Wellsian Utopia.

Donisthorpe's final adventure was a kind of Eight Men in a Boat cruise around the Mediterranean with Newnes and sundry other chaps. It was written up as "Down The Stream of Civilization", and even has a literary reference chess game in the dialogue on the first page: "...looking up from the chess-board, on which he was struggling with a rather nasty attack..." ("Then give him some Beecham's", they cried?). Here he is (on our left), aka "Jus - a Literary Failure", waiting to splice the mainbrace with some fellow hearties. Newnes, "The Commodore", is on the far right, and it was he who published the yarn in 1898.

Wordsworth Donisthorpe. Larger than life. You couldn't make him up, and he is a natural for dramatisation on stage or screen. Stephen Herbert has done just that with a performance, music and film production at the Museum of Moving Image, and

at the British Silents Festival in Nottingham . My own fantasy - recently alluded to in the blogosphere by a certain lady - is for a theatre piece in which Wordsworth, wit, chesser, politico, and undoubted charmer, meets the admirable Louise Matilda Fagan, and regards it as his masculine obligation to flirt (their age difference being just three years). We encountered her in episode 4, you will recall. She was a Fabian, and a more than decent player. Her father is in the bottom left-hand corner.

Admittedly Louise was abroad (Irish husband serving in India ) for some of the time, but when in London

So, Wordsworth Donisthorpe: what a character, who, in spite of his shortcomings (i.e. his politics IMHO), adds colour to the assembly of Rosenbaum's worthy gents. Possessed of "intellect and energy" - as Stephen Herbert puts it - who developed "a most powerful concept, that of reproducing filmed movement...which, when finally realised by others would revolutionise communications throughout the twentieth century." If we add to this his contibutions in those other fields of enquiry touched on above we see an exceptionally fertile brain at work, even if his efforts are now largely forgotten today.

Next week, for the conclusion of this series, we meet Anthony Rosenbaum; the artist himself.

Acknowledgments etc

|

| Published by the The Projection Box, but now out of print. |

Thanks again to Stephen Herbert and Mo Hearns. Their most recent research shows that WD had applied for a patent as early as 1868 when he was still at Cambridge. See here.

And thanks, yet again, to Paul Timson and Richard James for their help; and also to Tim Harding's Eminent Victorian Chess Players (2012) for Donisthorpe related info.

G.B.Shaw (1889) Mr Donisthorpe's Individualism

H. G. Wells (1905) A Modern Utopia

Donisthorpe's many writings are easily Googled, and Batgirl lists them, too. He has an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

And thanks, yet again, to Paul Timson and Richard James for their help; and also to Tim Harding's Eminent Victorian Chess Players (2012) for Donisthorpe related info.

G.B.Shaw (1889) Mr Donisthorpe's Individualism

H. G. Wells (1905) A Modern Utopia

Donisthorpe's many writings are easily Googled, and Batgirl lists them, too. He has an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

See all episodes, previous and subsequent, in this Rosenbaum series via our History Index.

Appendix follows after the jump

Appendix

G. A. MacDonnell's commentary on the Furniss Cartoon.

This was printed first in The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of April 11 1885, with an addendum (describing the chess problem on the ceiling) on April 18th.

The first line, on a previous page reads, "Punch last week (April 4th) did chess the honour of giving a..." and the piece continues:

Re Hoffer, above it says "sits calm and contemplative, the racy writer and acute analyst whose lucabrations (sic) weekly grace the pages of The Field, L.Hoffer".

Compare this with the later version in Knights and Kings of Chess (1894), which you can see in Winter, where it is edited to "sits calm and contemplative, the acute analyst, Field-marshal L Hoffer".

Appendix follows after the jump

Appendix

G. A. MacDonnell's commentary on the Furniss Cartoon.

This was printed first in The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of April 11 1885, with an addendum (describing the chess problem on the ceiling) on April 18th.

The first line, on a previous page reads, "Punch last week (April 4th) did chess the honour of giving a..." and the piece continues:

|

| click to enlarge |

Compare this with the later version in Knights and Kings of Chess (1894), which you can see in Winter, where it is edited to "sits calm and contemplative, the acute analyst, Field-marshal L Hoffer".

2 comments:

Wonderful. This is the sort of chess character I think we should be reading about. To me, he epitomizes a certain aspect of chess culture; players trying for immortality in clever but not always practical ways. Thanks for the article.

Jerry Spinrad

Thanks Jerry, you are welcome; and thanks also for taking the trouble to comment.

Post a Comment