In comments box to a post I'd written at the beginning of the February I said

"... I disagree with the idea that competitiveness breeds bad manners. Being a dickhead breeds bad manners"

Except that I didn't say that. What I actually said was,

"... I disagree with the idea that competitiveness breads bad manners. Being a dickhead breads bad manners"

"Crumbs" said our regular commenter Campion.

At the time I dismissed this as just a typo that needed no explanation but then a couple of weeks later I was thumbing through an essay I'd written in December of 2006 and found,

"As such, the area both reinforced existing delinquent behaviour and was a good breading ground for new forms of it ...."

A mundane example perhaps but nevertheless a reminder that we rarely make a mistake for the first time. In spelling as in life we repeat the same erroneous patterns over and over again.

Chess board errors hurt ... but not this much

And then there's chess.

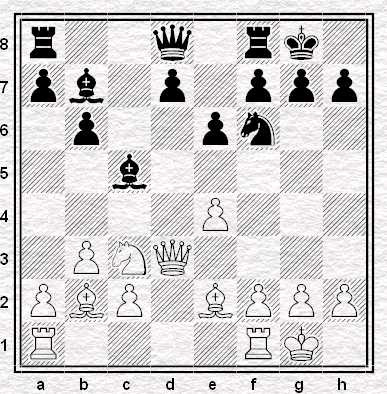

Of late I've been having a look at how I went astray in the position at the head of today's blog.

How did I go wrong? I'm still counting the ways but for a start there's miscalculation and the arguably greater sin of failing to realise that this was not the kind of position where playing a knight to the edge of the board was likely to work out happily.

Last time, T.C. suggested ... Qc8 as an preferable alternative to the game continuation ... Qxd5 agreeing with An Ordinary Chessplayer's comment to the original post. Avoiding the queen exchange in this way is Fritz's suggestion too.

I had in fact considered this sneaky queen move during the game but quickly dismissed the idea because although it defends my bishop on f5 and facilitates ...e5-45 - which was what I was trying to achieve with the erroneous ...Qxd5 and ...Na5 as played - it also gums up my back rank and in particular keeps the rook on a8 locked in. My scoresheet tells me I spent a total of five minutes on ... Qxd5 but I doubt I spent even ten seconds on ... Qc8. I certainly didn't pause long enough to consider how White might have responded had I played that move.

When I looked at the game with Fritz and saw ... Qc8 might have been the best move after all (our silicon friend suggests I would have been slightly better had I slid my queen one square to the right) I comforted myself with the thought that it was a slightly odd looking idea and at least I would now not overlook a similar oppportunity next time it cropped up. Then, a week after the game was played, I suddenly remembered an email encounter I'd had at the end of 2008.

I'd wanted to prevent e4-e5 with ... Qd8-c7 but was worried about Nc3-b5. Forget for the moment any question of whether the knight move is anything for Black to worry about. If you wanted to stop White advancing his king's pawn by moving your queen to the b8-h2 diagonal and were worried about the knight coming to b5, wouldn't it occur to you to think about moving her majesty to b8 out of Neddy's reach? Well I'm afraid it didn't occur to me even though I had several days to think about it.

And here's an other example that popped into my head just a few days ago. It's an over-the-board encounter, also from last December,

I played ... Kf7 fully realising that White could get his bishop out of trouble with a subsequent check from c4 but never even thinking to investigate how White could cope after ... Kf8.

It seems as if I have a chess pattern lodged in my brain that's really quite unhelpful. It's not that I consciously think "without exception I must connect my rooks" but that's how it turns out when I'm playing.

Learning something new - for example when moving knights to the edge is more likely to be a decent idea (see ABM III) - is hard enough at my age. Today's element of my bad move seems to me to be more about unlearning a faulty template I think I already 'know' - and that appears to be significantly more difficult to do something about.

Well, at least I'm having a go. Who knows ... maybe simply trying hard to understand our errors is what breads or even breeds success in the long run.

4 comments:

Gosh, that's some good sleuthing!

I think your analysis of this problem is very interesting.

Instead of this being a template problem I wonder if this is more a problem of the relative importance of principles in the position at hand. If you look back at Tom's Improve your chess I he said he gave the people he was coaching the 100 tips for better chess. After reading them he felt they were all good aims but prioritsing which were important in the position on board is difficult.

So the template "without exception I must connect my rooks" is really the principle "Rooks should be connected" (or something similar from Chernev) interpreted to it's full extent.

Will, you make a good point but I think it's a different one to what I'm exploring in the post.

Prioritising between conflicting principles (e.g. when is it a good idea to gum up your back rank) would indeed be tricky ... but when I'm playing it's not even occuring to me that I should be prioritising. I'm just ignoring half the equation.

It's an unconscious process. My conscious brain knows full well that "connect rooks" is not an absolute imperitive. Trouble is nobody's told my unconscious brain that yet.

btw: there'll be more on unconscious processes next time.

If you remove "bread" from it's dictionary, your spell-checker will underline it the next time you use it.

I agree that your chess problem is not a prioritization-of-principles problem. It's more a principle-exception problem. Maybe you need to adapt Chekhover's approach (see Think Like a Grandmaster): instead of looking for sacrifices first, as he did, you should consider "ugly" moves first. Your results would probably be much worse in the short term though.

There's a puzzle-book idea: What's the most ridiculous move?

Post a Comment